Le Chi Vien: Unraveling a Historical Miscarriage of Justice

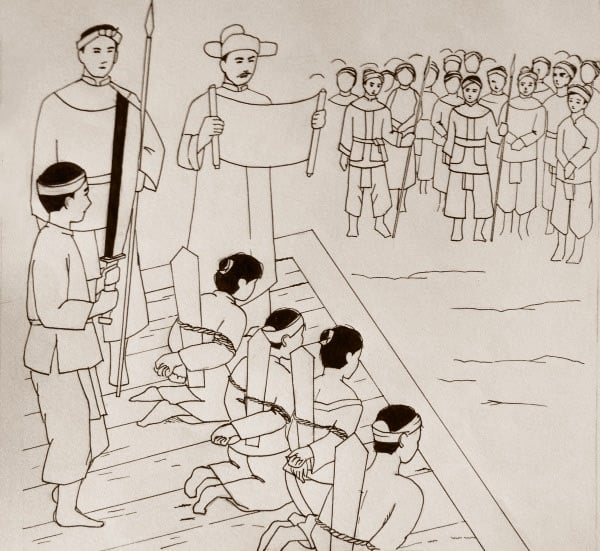

The Le Chi Vien case, one of the most notorious miscarriages of justice in Vietnamese history, took place in 1442 (Nhâm Tuất year). King Le Thai Tong died unexpectedly on the night of August 4 during his trip to the East after inspecting the armed forces at Chi Linh and visiting Nguyen Trai at Con Son. The court hastily concluded that Nguyen Trai’s wife, Nguyen Thi Lo, poisoned the king, leading to the execution of Nguyen Trai and three generations of his family just 12 days later.

Dai Viet Su Ky Toan Thu records: “When the king traveled to the East and reached Le Chi garden, he stayed up all night with Nguyen Thi Lo and then passed away… Everyone believed that Nguyen Thi Lo killed the king.”

However, historian Le Quy Don, in his 18th-century work Dai Viet Thong Su, noted that “When King Thai Tong traveled to the East and fell critically ill, Lieutenant Trinh Kha stayed by his side, constantly attending to his medication.”

19th-century historians of the Nguyen Dynasty, in Kham Dinh Viet Su Thong Gam Cuong Muc, also recorded the king suffering from malaria. Despite this, many blamed Thi Lo, believing she was involved in the king’s death and that Nguyen Trai should be held accountable for his wife’s actions. This was considered unjust.

Evidently, the king passed away in a “critical” state, with Lieutenant Trinh Kha by his side attending to his medication all night, not just Nguyen Thi Lo.

So, why did the court incriminate Nguyen Trai and his wife? Historians have begun shedding light on the reasons. Le Thuoc was the first to re-examine the case in his 1957 article “Re-examining the Nguyen Trai Case” published in the Van Su Dia magazine. In 1980, after UNESCO recognized Nguyen Trai as a World Cultural Celebrity, new research emerged. Notably, at a scientific workshop on Le Nghi Hoc Si Nguyen Thi Lo held in Hanoi in 2002, scholars used new sources to confirm that Nguyen Trai and Nguyen Thi Lo had no connection to the king’s death; they were, in fact, victims themselves. This also exposed the inherent weaknesses of the feudal regime, where clan exclusivity led to selfish decisions.

Why Was the Blame Placed on Nguyen Trai and His Wife?

Survivors of the Tragedy

History does not clearly record the identities and exact number of victims of this tragedy beyond Nguyen Trai and Nguyen Thi Lo.

According to the genealogy of the Nguyen clan in Chi Ngai (Chi Linh), Phuong Quat (Kinh Mon), and Nhi Khe (Thong Tin, Hanoi), Nguyen Trai had five wives. His first wife was Tran Thi Thanh, followed by a woman from the Phung clan (from Nguyet Ang, Thanh Tri, Hanoi). His third wife was Nguyen Thi Lo (from Hai Trieu, Nghe Thien, now Hung Ha, Thai Binh). His fourth wife was Pham Thi Man (from No Ve, Thuy Phu, Phu Xuyen, Hanoi), and his fifth wife was Le Thi (from Chi Ngai village, Cong Hoa, Chi Linh).

Nguyen Trai had seven sons and a daughter. His sons were Nguyen Phu (also known as Nguyen Hong Quy or Hong Quy), Nguyen Khue, and Nguyen Ung (with Tran Thi Thanh); Nguyen Thi Tra, Nguyen Ban, and Nguyen Tich (with the Phung clan wife); and Nguyen Anh Vu (with Pham Thi Man). His only daughter, Nguyen Thi Dao, was reportedly mute.

When the tragedy struck, Nguyen Trai’s parents, Nguyen Phi Khanh and Tran Thi Thai, were already deceased and thus not implicated. Phi Khanh had two wives and seven children. The first wife bore five sons, with Nguyen Trai being the eldest. The three brothers sharing the same mother as Nguyen Trai were noted as “vo khao,” suggesting they might have been killed.

History Does Not Clearly Record the Identities and Number of Victims Beyond Nguyen Trai and Nguyen Thi Lo

Of Nguyen Trai’s three brothers, Nguyen Phi Hung (full-blooded brother) accompanied their father to China in 1407. The other two, Nhu Soan and Nhu Trach, escaped the tragic fate and returned to Cam Nga, Dong Son (Thanh Hoa). Nhu Trach settled in Bong village, Vinh Tan, Vinh Loc, giving rise to two branches of the Nguyen clan.

Of Nguyen Trai’s five wives, only the first wife, Tran Thi Thanh, who lived to be 62, and the fourth and fifth wives, Pham Thi Man and Le Thi, survived. Tran Thi Thanh passed away on the 16th day of the eighth lunar month, coinciding with the tragic event in 1442, and she may have been executed. Nothing is mentioned about the second wife from the Phung clan in the genealogy. Among Nguyen Trai’s seven sons, only two from the first wife, Nguyen Phu and Nguyen Khue, and two from the Phung clan wife, Nguyen Ban and Nguyen Tich, are not accounted for, possibly falling victim to the execution as well.

According to Mr. Nguyen Van Cuong, Deputy Manager of the Con Son-Kiep Bac Relic Complex, three sons and a daughter of Nguyen Trai survived. Nguyen Phu, the son of the first wife, escaped to Phu Dam (now Phu Khe, Tu Son, Bac Ninh), continuing the branch of the Nguyen Trai clan there.

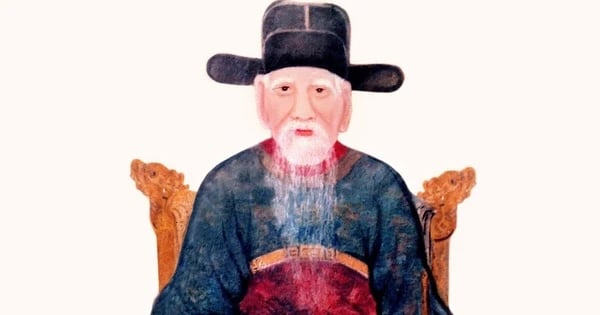

Nguyen Thi Lo

Nguyen Anh Vu, the son of Pham Thi Man (fourth wife), was taken by his father’s disciple, Le Dat, to the Bồn Man region to escape the pursuit. After the case subsided, Man returned to Du Quan village, Ngoc Son district, Tinh Gia district, and gave birth to Anh Vu. To ensure safety, Vu changed his surname to his mother’s, becoming Pham Anh Vu. In 1464, King Le Thanh Tong exonerated Nguyen Trai, and Pham Anh Vu, as the only representative of the family, received the royal decree. He married twice and had seven sons, restoring the family lineage in places like Nhi Khe, Phu Xuyen (Hanoi), Chi Ngai (Hai Duong), Hai Anh (Hai Hau, Nam Dinh), Xuan Duc (My Hao, Hung Yen), and Du Quan (Xuan Lam, Tinh Gia, Thanh Hoa).

Nguyen Thi Dao, Nguyen Trai’s only daughter, was reportedly saved by an eunuch during the family’s catastrophe.

Additionally, Le Thi, Nguyen Trai’s fifth wife, also survived and fled to Phuong Quat (Kinh Mon), where Nguyen Nang Doan was born, contributing to the formation of many Nguyen clan branches in Kinh Mon and Trieu Ben (Dong Trieu, Quang Ninh).

The Le Chi Vien case took the lives of many in Nguyen Trai’s clan, but not all met a tragic end. Later, when the truth prevailed, they restored their fortunes and actively contributed to the nation’s development.