In fact, a child’s confidence can be recognized through their choice of words. Parents should understand the psychology behind these four commonly used phrases and work together to ignite their child’s confidence.

“I can’t do it/I’m sure I can’t do it well”

When a child says this, it’s like a student intentionally not studying for a test and giving themselves a failing grade. Afterward, they can confidently say, “See, I just didn’t take it seriously!” The underlying fear is that trying their best and still failing will hurt their self-confidence, so they use this as a defense mechanism to protect their fragile self-esteem.

In this case, parents should recharge their child’s mental energy and help boost their confidence.

Break down tasks: Divide large tasks into smaller, manageable ones within the child’s ability, such as changing “learning to ride a bike” to “practicing balance for 5 minutes.”

Rebuild language: Change “I believe you can do it” to “If you fall, we’ll find a way to adapt”.

Offer small rewards: If the child makes a mistake, summarize a “list of achievements” with them – “This time you know not to brake too hard!”

“I’m so stupid/I’ll never learn”

This is essentially “emotional recall” of past failures, similar to fearing to touch a hot stove after getting burned. The brain tends to recall old experiences and uses them to scare itself.

In reality, the water temperature is different now, but the brain always likes to bring up old stories.

A specialist shared his experience; when he was in elementary school, he went up to the board to solve a math problem but couldn’t. The teacher criticized him in front of the class, and his brain processed it as “I’m not good at math.” This influenced him for the rest of his life, and every time he failed a math test, an old man would appear and say, “You’ll never be good at math.”

Past failures, if not properly addressed, can become “psychological imprints.” So, instead of easily labeling, remember the child’s strengths, “Do you remember how you learned to skip rope in three days?”, say “You’re still not proficient” instead of “You’ll never learn”, and provide realistic feedback when they’re practicing, “Your wrist movement is better than last time!”

“It’s all their fault/If it weren’t for…”

By blaming others and external factors, the child avoids facing their fears. If they frequently say, “I’m not good enough”, they may develop an external control orientation, believing that success or failure depends on luck, others, or the environment. When faced with failure, they tend to default to “It’s all their fault” or “I’m unlucky”, and rarely consider making changes.

However, a child’s personality is not yet fully formed and can be changed through intervention.

For example, use dolls to reenact conflicts and encourage the child to broaden their perspective, “What would Teddy think about this?” Or foster multiple perspectives, “What would happen if…?”

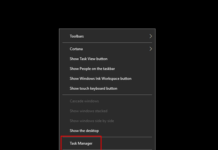

Play a responsibility-sharing game. For instance, if the child is criticized by their teacher for forgetting their homework, they might typically say, “It’s Mom’s fault for not reminding me!” Here, the parent can take out a yellow, red, and green fluorescent pen and draw three concentric circles on a piece of paper:

– The outermost circle is red: “Mom didn’t remind you (other factors), but who is responsible for reminding you about your homework?”

– The middle circle is yellow: “It rained today and your bag got wet. Maybe the homework stuck together (environmental factors).”

– The innermost circle is green: “What can we do? For example, put the homework in a separate file before going to bed (self-thinking).”

By peeling back the layers like an onion, the child discovers that besides blaming others, they can also control the green part. Finally, the parent cuts out the paper and sticks it on the fridge, using it to analyze and color-code each time an issue arises.

“I don’t care…”

This is “decision-making fear”! It’s like a child standing in a tea shop, hesitating for half an hour, and finally saying, “I’ll have what my friend is having” – afraid to make the wrong choice and be rejected, so they give up their right to choose.

However, suppressing real-life needs for an extended period can lead to the formation of a dark personality. On the surface, the child appears obedient and well-behaved, but deep down, they may be relieving stress through subtle methods like nail-biting or hair-twirling. Accumulated stress can also explode into panic attacks or compulsive behaviors (such as constantly checking doors and windows).

Therefore, parents should empower their children to make choices from an early age, fostering their decision-making skills.

Limited choice method: Start practicing with two options. Instead of asking, “What do you want for dinner?”, ask, “Do you want rice or noodles?” instead of saying, “Let’s wear red socks today!”, ask, “Do you want to wear red or yellow socks?”

Establish a testing area: Let the child decide on a family activity each week, even if it’s just watching ants move.

Play the traffic light game: Green means immediate action, yellow means discussing risks, and red means the parent provides a safety net.

For example, the child wants to use their New Year’s money to buy a telescope but is worried about choosing the wrong model.

Green card action: Decide immediately to “buy binoculars” (basic models with low risk)

Yellow card discussion: Analyze “Should I also buy a tripod?” “The advantage is more stable observation, and the disadvantage is difficult to carry”.

Red card assurance: Parents check the trusted online shopping platform to exclude unreliable suppliers.

In this way, the child experiences the joy of making their own decisions (green card) and learns to consider pros and cons (yellow card). There’s also a safety net (red card) at critical junctures.

The discouraging words children use are like little guards protecting their hearts, shielding them from the hurt of failure. But deep down, they also yearn to move forward.

So, parents should first create a sense of security for their children and then, through the intervention of the “cognition-behavior-emotion” triangle, gradually break down the rigid structure of low self-esteem and rebuild a positive communication pattern.