According to Science News, a New England Journal of Medicine study published in late June revealed promising results. A year after treatment, 10 out of 12 participants no longer required insulin injections as they were able to produce sufficient insulin after the initial transplant.

“This is a groundbreaking achievement,” said Giacomo Lanzoni, a researcher at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami. He highlighted the potential of laboratory-grown cells, suggesting that this approach could be scaled up to restore insulin production for many people living with the disease.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. The lack of insulin leads to a buildup of sugar in the blood, causing damage to the body.

Felicia Pagliuca, the study’s author and Senior Vice President at Vertex Pharmaceuticals, emphasized the critical importance of insulin, stating, “Life cannot exist without insulin.”

For over a century, insulin injections have been the lifeline for people with this form of diabetes. However, supportive tools like glucose monitors and insulin pumps are not perfect solutions. Blood sugar levels need to stay within a very narrow range; too high and it can damage the kidneys, nerves, and eyes, and too low can lead to fainting or life-threatening complications.

“There is a real need for new therapies,” Pagliuca added.

In 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a method using pancreatic cells from deceased donors to replace the lost cells. However, this approach is limited by the availability and quality of donor organs.

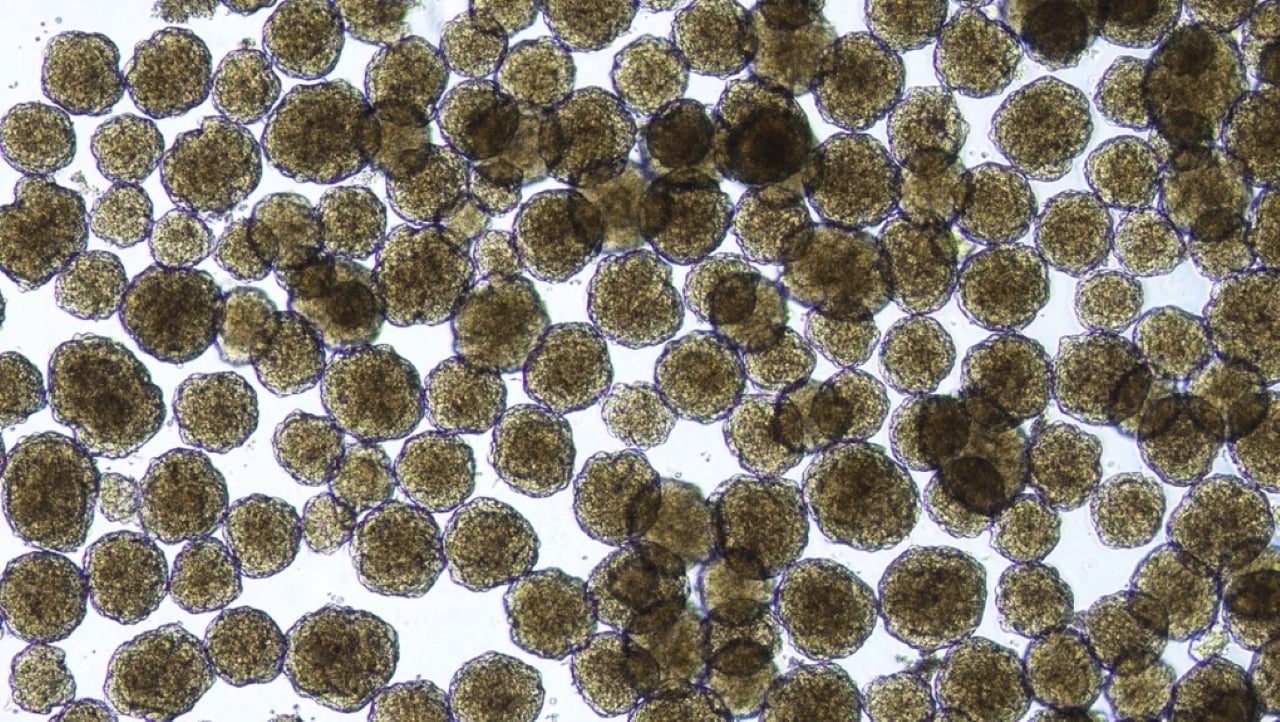

To address this challenge, Vertex developed a technique to culture pancreatic islet cells from human stem cells, using a mix of nutrients and chemicals. Rather than transplanting these cells into the pancreas, they are injected into the liver, where they function effectively.

In a clinical trial involving 14 patients, doctors transplanted hundreds of millions of these cultured islet cells into a vein. Pagliuca explained that the cells immediately became active, sensing blood sugar levels and producing insulin accordingly. After a full dose of the treatment, named zimislecel, 10 out of 12 patients no longer required insulin injections a year later. The remaining two participants reduced their insulin needs by 70%.

Tom Donner, director of the Johns Hopkins Diabetes Center, commented on the significance of this achievement: “Being free of insulin dependence is a remarkable accomplishment.” He added that it significantly reduces the psychological burden on patients living with the disease.

While most patients tolerated the treatment well, Vertex reported two unrelated deaths and some side effects. One death was due to surgical complications, and the other was related to a pre-existing brain injury. Side effects included diarrhea, headaches, nausea, and Covid-19 infections, largely due to immunosuppressant medications required to prevent the body from rejecting the new cells. Patients need to continue taking these medications to protect the transplanted cells.

Lanzoni cautioned that “immunosuppression is not trivial,” and he hopes that future research will lead to therapies that do not require long-term use of these drugs.

Vertex is now expanding its trial to 50 patients, most of whom have already received the full treatment dose. Data from this larger group will form the basis of the company’s application to the FDA for approval in 2026.